In the previous article, I explained how I formed my psychological contract with my former host country and how it affected me.

All the personal messages I got showed that it resonated with quite a few people!

The truth is: we’re not insensitive. The behavior of the people we’re interacting with influences us!

Whether you like it or not, whether you want it or not, they’ll change you. For the better or for the worse.

When people encourage your initiatives and support you if only by a smile, a caring look or a kind attention, you feel more confident and more assertive.

On the opposite, when you’re constantly ignored or told off, you withdraw and lose your self-confidence.

A mother of two young children wrote to me:

“I’m working hard just to not let them (the local people) change us, especially my sons. I don’t want them to change their behavior just to settle in a culture that I really don’t like. Whenever I see people coming towards me to talk about my children, I know it’s to complain about them! Because they are too noisy or too rude.”

Another friend mentioned:

“In my country we’re used to greet each other even when we never met before. Here I only get weird looks when I say hello. So I don’t do it anymore.”

Without being mindful of what’s happening in the background – the violation of your psychological contract – you can be tempted to deny your emotions or to overreact, either of which is not a healthy response.

So what can you do to avoid falling in that trap?

Let me first state here that I don’t pretend to give the definitive answer in this article. I doubt there is any. The question is complex and reaches into diverse areas such as cultural values and identity.

But I’ll try to give you some actionable tips to work with in order to improve your emotional well-being.

Before we touch upon those concrete actions, let’s dig deeper into the psychological contract with a country.

I believe it’s important in order to better understand how it is formed and pay closer attention at the elements you want to integrate or not. Note that this my view and I’d welcome any feedback and suggestions to improve the expression of this concept.

Definition (derived from Rousseau and adapted to our expat context )

The psychological contract is comprised of your belief in perceived promises which will govern the terms and conditions of your relationship with the country.

Let’s look in details at the components of this psychological contract.

Who are the parties in case of a psychological contract with a country?

Yourself on one side and two categories of people on the other side:

1/ the professionals: people representing the state (police, justice, school, administration, immigration), doctors, business people

2/ the common people in the streets, in the shops, at the playground, people in your neighborhood.

It’s really ALL the people you meet randomly. You don’t know them and you’re not brought in contact with each other because of a financial or professional transaction.

I’d like to underline 3 points:

a. It can’t be only one person of each category otherwise it means that you have a psychological contract with that person, not with a country.

b. It can’t be family either (for example in-laws if you’re part of a mixed marriage) because you’ll have a particular psychological contract with your in-laws and it’ll be different from the one with a country.

c. The case with friends is a grey zone: when you arrive in a new country, you don’t have friends yet (most often). You’ll eventually make friends (hopefully) and they’ll influence your perception of the country, associating fond memories to local places.

However, I would be very mindful of considering your friends as a group but not each one individually. First, you have to make a distinction: are those friends native from the country? And if one friend betrays you, you can’t consider that all your local friends are unreliable. You may also wonder: who do I consider as a close friend or a simple and nice acquaintance? Close friends even in your home country are not legion. Not more than a few. How can this be representative of a population?

A contract with a country refers to a vast array of people and not a few isolated interactions.

What are the perceived promises?

According to Rousseau, the perceived promises can be:

- Interpretation of previous patterns

Example: Each time you greet somebody in the street, they answer. You might feel that this promise has been violated next time you greet a stranger and don’t get any reaction or even worse: a weird look.

- Witness others’ experience

Example: In some countries, corruption is the rule. If it’s well known that foreigners generally need to pay x amount of money to get an Internet connection within 10 days, you assume that you’ll get the same service by paying the same amount of money.

- Deduction from values you take for granted (fairness, good faith, reciprocity…)

Example: If you give a hand to someone, you expect they’ll help you next time you need it. If you’re polite with someone, you think they’ll appreciate. Well, think again. Chinese and Dutch people become suspicious when dealing with a person they perceive as being over-polite.

- Explicit promise through laws or public statements

Example: In France for example, the motto is “Freedom, Equality, Fraternity” (written on hundreds of monuments, city halls, churches and palaces of justice).

When you come as a foreigner, you don’t know what to expect. But reading such a powerful and explicit message sounds like a strong promise.

However you’re going to interpret those words “Freedom, Equality, Fraternity” with your own schema, your own cultural background.

Freedom: for some people it could mean walking naked in the streets or wearing a burka.

Equality: In France, this is translated by a fairly equal access to education. Through a scholarship system based on the parents’ income, you can study in any school provided you pass the required academic tests. This doesn’t mean that anybody is entitled to go to university for example.

Fraternity: When my daughter cut her forehead after falling from the stairs at my parents’ house in France, we rushed to the emergency department. She immediately got treated and we never had to pay anything although I had provided my parent’s address and handed all identification documents to trace us back.

But can you imagine the face of the guy queuing after you at the local bakery if you miss 50 cents to buy a baguette and you ask him for help? Talk about fraternity!

And finally I’d like to add:

- Stereotypes

What role do stereotypes play in shaping the promises when you come to live in another country?

French people smell bad. They’re snobby and arrogant. Americans are obese, don’t speak any foreign languages, don’t know where to place Belgium on a map. Mexicans are lazy, illegal immigrants and carry a giant sombrero. Germans live for drinking beer, eating sausages and don’t like children.

I hear you saying: “Oh Anne, those stereotypes are ridiculous. I don’t believe in those preconceptions, of course not.”

Well, those examples are quite coarse but stereotypes are everywhere: trailing spouses are women. They spend all their time shopping and going to the manicure. Expats live in big villas with swimming pool, house maids, cook, gardener and driver.

But there is more. It’s not only about the stereotypes you have of others. It’s also about the stereotypes YOU carry from your home country. What kind of “promise” will be formed in the mind of the local people?

And how does it affect you?

According to Carole Dweck, Stanford University psychology professor, stereotypes fill people’s mind with distracting thoughts

“Am I really arrogant by asking this? I certainly don’t want people to think that I don’t take showers”. She mentions that “people usually aren’t aware of it but they don’t have enough mental power left to do their best.”

Here is a striking example:

Researchers at Stanford University conducted the following experiment. They took a group of black students and a group of white students giving them the same standardized test. When the researchers told them that it measured IQ, white students performed better than black students. When they mentioned it was designed to measure their problem solving skills, both groups performed equally!

Similar experiments have been conducted with boys and girls about their abilities in mathematics. Guess who performed better when the stereotype was mentioned?

In “Exploring the Negative Consequences of Stereotyping”, Toni Schmader and Jeff Stone, both social psychologists at the University of Arizona, studied a phenomenon called “stereotype threat.”

They mentioned “that the individuals who are most susceptible to these effects are those who are likely to be the most motivated to do well and most interested in maintaining a positive image of their group.”

Aren’t most expatriates in that situation? Because we’re very conscious that if we, as an individual, act badly, our whole group of compatriots will be condemned?

More interesting: “These two researchers believe that the key to dismantling stereotype threat may be increased awareness that this phenomenon exists.” Does it ring a bell?

Understanding and dismantling stereotypes allows us to form more realistic psychological contracts, resulting in less disappointment and having a greater sense of control over our reality.

Let’s summarize: a psychological contract is a set of reciprocal and promised obligations generating violent reactions like distrust possibly leading to the dissolution of the relationship itself when violated (Rousseau 1989).

So here are 5 tips to help you mitigate the adverse effects of psychological contract violation.

1. Be mindful of the presence of your psychological contract

How do you form it? What do you want to integrate? Where do you get the promises from?

2. Sharpen your stereotypes awareness

What kind of stereotypes do you have of your host country? Do you know the stereotypes you carry from your home country?

Make a quick search or ask around. You might be surprised!

3. Give yourself a crash course in the history of the country

“Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardonner.”

“Understanding everything is forgiving everything” Leo Tolstoi Click to tweet

Reactions and behaviors of native people have been ingrained and passed on from generation to generation. History offers some great answers to decipher those patterns.

4. Think of your mindset when facing rejection

Being rejected hurts. There’s no doubt about that. But how do you process it? Does it haunt you for days? Do you feel paralyzed to act again? Do you feel worthless?

Or do you actively look for ways to solve the problem, learn the lesson from this experience and move on?

5. Look actively for support groups

Look for a supportive community (whether through sports, arts, music…) sharing your values. I can’t emphasize it enough. It’s not only for yourself but for your children.

“It takes a village to raise a child” according to an African saying. The older they grow, the more they become sensitive to others’ opinions.

Which tip are you going to try first? Which one do you find the most useful? Any other suggestions? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below.

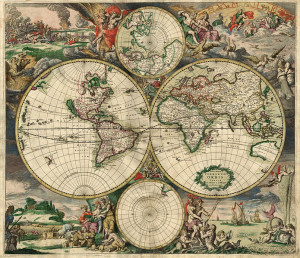

Credit image Wikimedia Commons, Credit music pianosociety