You may not have thought about it this way, but you make “psychological contracts” in your head all the time.

I bet you even know what I mean by psychological contract before I explain it because the idea is simple, obvious and true.

Here is a prime example.

Suppose you do something for your partner: you cook a great dinner. You spend time choosing the perfect ingredients, you carefully monitor the cooking, you arrange the table with some decorations. When it’s finally ready, you call your partner to enjoy the dinner together.

….

You call again.

No reaction.

The dinner is getting cold.

Twenty minutes later, he/she comes, sits down and starts to eat while checking his/her emails.

It hurts.

At best, you feel a twinge. At worst, you explode, burst into tears or leave.

Do you know why?

Because it’s a violation of your psychological contract.

You had made in your mind the mental picture that if you’d prepare dinner and – even more – put a lot of efforts into something special, you would get some form of acknowledgment. You would expect your partner to appreciate your efforts, respect your work, come on time and show you some affection for it, as a form of reciprocity.

But this whole “procedure” hasn’t been described in a written form. It’s not mentioned in your marriage contract. Nowhere can you find that when you prepare a nice meal, your partner has to come on time and show some form of gratitude or appreciation. Neither you nor your spouse signed such a declaration. It’s your expectation based on your education.

This is called a psychological contract.

I’m inspired to use this concept by analogy with the theory developed in Organizational Behavior around employer-employee relationships. The latter according to Levinson et al (1962) defines the psychological contract “as comprising mutual expectations between an employee and the employer.” In our context of course, replace employee and employer by “the two spouses”.

Note what comes next: “These expectations may arise from unconscious motives and thus each party may not be aware of the own expectations yet alone the expectations of the other party”. And if this was the reason of so many misunderstandings, failed marriages, tragic depressions?

Why is it important to understand this concept? After all, you’ve lived for years without knowing this terminology. I believe there is a power in putting words to emotions, intuitions, feelings. As famous French psychoanalyst Francoise Dolto says, there is a spark when we notice the coincidence between what we feel and what we say.

Psychological contracts are often implicit

Have you ever told your spouse: because I’m going to cook, you’re going to come on time and show appreciation of what I’ve made?

I doubt it. It’s so obvious that you think you don’t need to verbalize it.

In fact, it’s even the opposite: it’s so obvious that it hurts to formulate it.

You feel embarrassed to explain “obvious” transactions because it looks like you’re begging for something or justifying yourself. But what is obvious for you might very well not be obvious for someone else. Your partner has his/her psychological contract too. How can you know what he/she thinks?

Even worse: sometimes, you don’t even know what to expect yourself. When Caroline left Tasmania after living there for 18 months, she was extremely surprised by the intensity of the feelings some of her newly made friends showed her. They organized farewell parties, they had tears in their eyes, they were truly affected even if they had only known her for such a short period of time. She didn’t get such endearment even in her own country where she spent 30 years! This was exceeding her expectations. Her friends had obviously in their minds a different version of psychological contract for their friendship than she did.

Psychological contracts are shaped by our culture

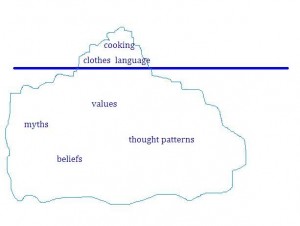

Let’s come back for a second to the iceberg model of culture developed by anthropologist Gary Weaver.

The emerged part of the iceberg, the smaller one, is composed of the visible parts of culture: food, clothes, language, architecture to name a few examples. But the submerged part of the iceberg, the most important one, contains the values, beliefs, myths and thought patterns of culture. Those elements are much difficult to apprehend because they’re diffuse and very often implicit.

Let’s take a simple example. In many cultures, girls have been (or still are) conditioned from a very early age to take care of household tasks: preparing dinner, washing and ironing clothes for example. Boys raised in such families do not know any other kind of life. For both genders, this is considered as absolutely normal. Girls don’t expect to get some kind of recognition and boys don’t even think about giving some appreciation.

There is no immediate form of reciprocity.

In our Western societies, there has been a strong push in the last 50 years towards equality. Men get father’s leave for the birth of a child, women have achieved more prominence on company boards. Preparing dinner or changing diapers is not an area exclusively reserved to women any more.

Can you imagine the clash if a man from the firstly described culture marries an American/French woman? Do you see the difference in their respective psychological contract?

I’d like to go even further. We just saw how the notion of reciprocity is important.

But even reciprocity can be tricky. Take a look at the following example.

In this article, you’ll learn that Dutch people distrust people who are too polite. They find this behavior suspicious, even fake. If you are too polite, you must want to take advantage of them. So they think.

Generally speaking, when I’m in a foreign country, I tend to be more polite because I want people to accept me, to think that I have good manners and that I respect them. In the Dutch speaking part of Belgium where I lived for 15 years, I did not always find that native speakers were specially polite. I would even say rude at times. And that would make the problem even worse. Feeling that I was not very well accepted would make me even more courteous. Was this different interpretation of politeness the reason of my discomfort? Do you see the misunderstanding and the vicious circle?

The rule of reciprocity is NOT always TRUE.

Psychological contracts evolve over time.

Psychological contracts can change over time. The best example of this is the psychological contract you have with your children.

When your children are under 2 years old, you happily feed them, dress them up, give them the bath. In return, your biggest reward is a smile.

When they’re around 10 years-old, you (happily) prepare the meal but expect them to eat by themselves. You provide the clean clothes but don’t dress them up and would be deeply disappointed if you had to.

When they turn 25 years old, you hope they’ll buy their clothes and definitely get dressed on their own. If you prepare a meal, it’s not by necessity any more. It’s by pleasure, as a gift.

Later on, when you’re old, you’ll be waiting for them to invite you for dinner. And you’ll have in mind that they’ll care about you if you have health problems. You might even need their help to get dressed!

This is how far psychological contracts can evolve.

Now back to your relationship.

Do you remember when your psychological contract with your spouse last tipped ? Was it when you moved? Was it when you accepted to give up your job only to realize a few months later you would have to be a stay-at-home mom? Was it when you lost your financial independence and discovered that your partner considered their salary as their own money exclusively? Or was it when you remained stuck at home lonely for weeks because of a traveling partner while you expected to spend more time together?

We make psychological contracts in our head all the time. And they can stay hidden there for years. But when a big change occurs – and a move abroad is a huge change – those psychological contracts stand out. This is why they play such a big role for expatriates.

What kind of psychological contract do you have with your spouse? your children? your parents? Have you ever thought about it?

There is great value in taking what was once implicit and making it explicit as a tool for self-awareness and self-development.

* Reference: Psychological contracts, Jacqueline Coyle-Shapiro and Marjo Riitta Parzefall (2008)

Credit image Wikimedia Commons, Credit music pianosociety